26. Risk and Model Uncertainty#

26.1. Overview#

As an introduction to one possible approach to modeling Knightian uncertainty, this lecture describes static representations of five classes of preferences over risky prospects.

These preference specifications allow us to distinguish risk from uncertainty along lines proposed by [Knight, 1921].

All five preference specifications incorporate risk aversion, meaning displeasure from risks governed by well known probability distributions.

Two of them also incorporate uncertainty aversion, meaning dislike of not knowing a probability distribution.

The preference orderings are

Expected utility preferences

Constraint preferences

Multiplier preferences

Risk-sensitive preferences

Ex post Bayesian expected utility preferences

This labeling scheme is taken from [Hansen and Sargent, 2001].

Constraint and multiplier preferences express aversion to not knowing a unique probability distribution that describes random outcomes.

Expected utility, risk-sensitive, and ex post Bayesian expected utility preferences all attribute a unique known probability distribution to a decision maker.

We present things in a simple before-and-after one-period setting.

In addition to learning about these preference orderings, this lecture also describes some interesting code for computing and graphing some representations of indifference curves, utility functions, and related objects.

Staring at these indifference curves provides insights into the different preferences.

Watch for the presence of a kink at the \(45\) degree line for the constraint preference indifference curves.

We begin with some that we’ll use to create some graphs.

# Package imports

import numpy as np

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import rc

from scipy import optimize, stats

from scipy.io import loadmat

from matplotlib.collections import LineCollection

from numba import njit

26.2. Basic objects#

Basic ingredients are

a set of states of the world

plans describing outcomes as functions of the state of the world,

a utility function mapping outcomes into utilities

either a probability distribution or a set of probability distributions over states of the world; and

a way of measuring a discrepancy between two probability distributions.

In more detail, we’ll work with the following setting.

A finite set of possible states \({\cal I} = \{i= 1, \ldots, I\}\).

A (consumption) plan is a function \(c: {\cal I} \rightarrow {\mathbb R}\).

\(u: {\mathbb R} \rightarrow {\mathbb R}\) is a utility function.

\(\pi\) is an \(I \times 1\) vector of nonnegative probabilities over states, with \(\pi_ i \geq 0, \sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i = 1\).

Relative entropy \( \textrm{ent}(\pi, \hat \pi)\) of a probability vector \(\hat \pi\) with respect to a probability vector \(\pi\) is the expected value of the logarithm of the likelihood ratio \(m_i \doteq \Bigl( \frac{\hat \pi_i}{\pi_i} \Bigr) \) under distribution \(\hat \pi\) defined as:

or

Remark: A likelihood ratio \(m_i\) is a discrete random variable. For any discrete random variable \(\{x_i\}_{i=1}^I\), the expected value of \(x\) under the \(\hat \pi_i\) distribution can be represented as the expected value under the \(\pi\) distribution of the product of \(x_i\) times the `shock’ \(m_i\):

where \(\hat E\) is the mathematical expectation under the \(\hat \pi\) distribution and \(E\) is the expectation under the \(\pi\) distribution.

Evidently,

and relative entropy is

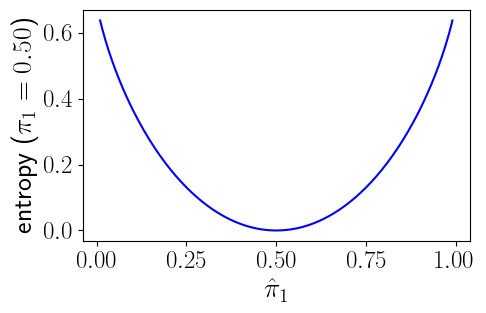

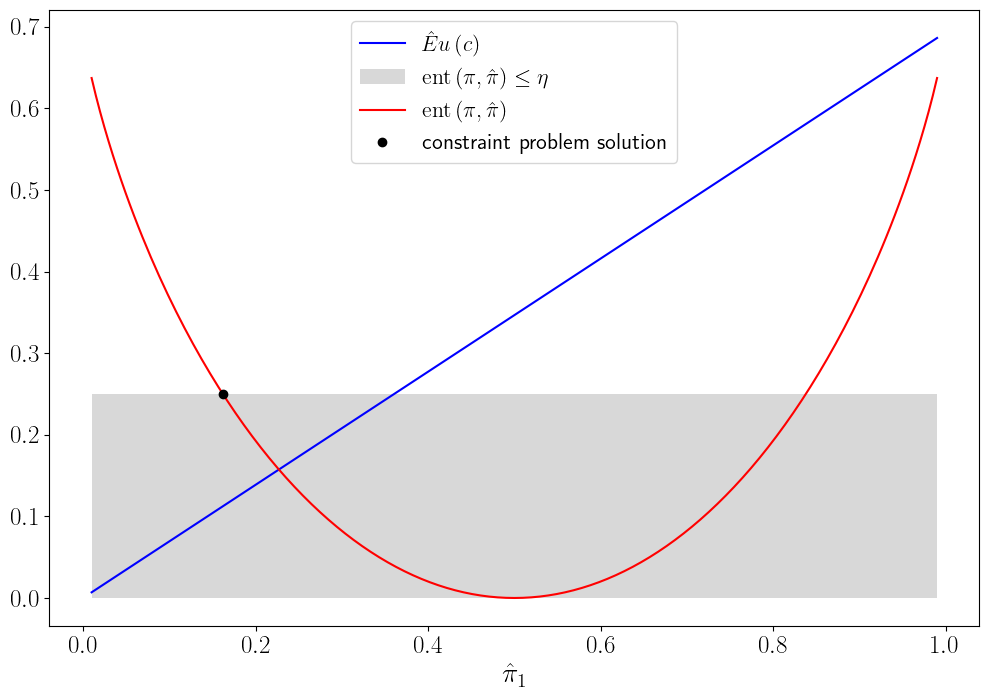

In the three figures below, we plot relative entropy from several perspectives.

Our first figure depicts entropy as a function of \(\hat \pi_1\) when \(I=2\) and \(\pi_1 = .5\).

When \(\pi_1 \in (0,1)\), entropy is finite for both \(\hat \pi_1 = 0\) and \(\hat \pi_1 = 1\) because \(\lim_{x\rightarrow 0} x \log x = 0\)

However, when \(\pi_1=0\) or \(\pi_1=1\), entropy is infinite.

Fig. 26.1 Figure 1#

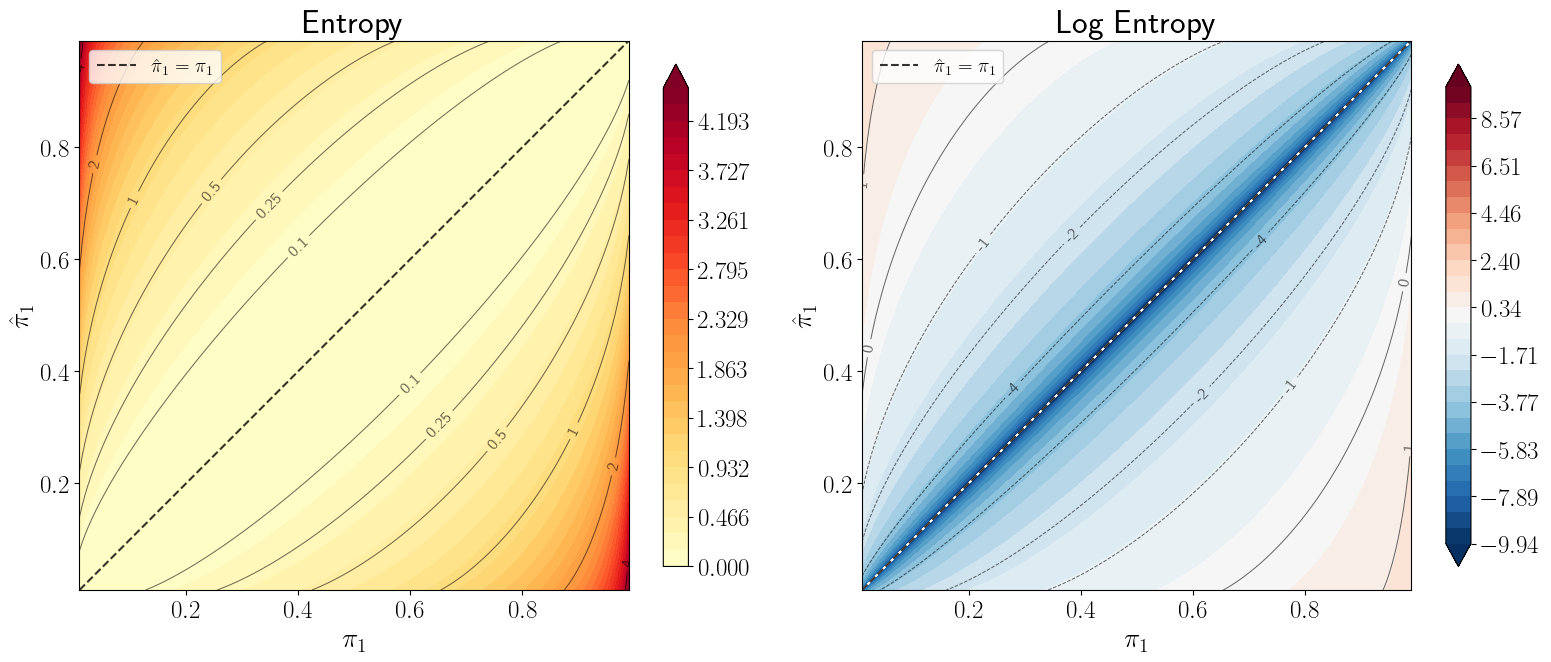

The heat maps in the next figure vary both \(\hat{\pi}_1\) and \(\pi_1\).

The left panel plots entropy, which equals zero along the diagonal \(\hat{\pi}_1 = \pi_1\) and grows as \(\hat{\pi}\) diverges from \(\pi\).

The right panel plots the logarithm of entropy

26.3. Five preference specifications#

We describe five types of preferences over plans.

Expected utility preferences

Constraint preferences

Multiplier preferences

Risk-sensitive preferences

Ex post Bayesian expected utility preferences

Expected utility, risk-sensitive, and ex post Bayesian preferences are each cast in terms of a unique probability distribution, so they can express risk-aversion, but not model ambiguity aversion.

Multiplier and constraint preferences both express aversion to concerns about model misppecification, i.e., model uncertainty; both are cast in terms of a set or sets of probability distributions.

The set of distributions expresses the decision maker’s ambiguity about the probability model.

Minimization over probability distributions expresses his aversion to ambiguity.

26.4. Expected utility#

A decision maker is said to have expected utility preferences when he ranks plans \(c\) by their expected utilities

where \(u\) is a unique utility function and \(\pi\) is a unique probability measure over states.

A known \(\pi\) expresses risk.

Curvature of \(u\) expresses risk aversion.

26.5. Constraint preferences#

A decision maker is said to have constraint preferences when he ranks plans \(c\) according to

subject to

and

In (26.3), \(\eta \geq 0\) determines an entropy ball of probability distributions \(\hat \pi = m \pi\) that surround a baseline distribution \(\pi\).

As noted earlier, \(\sum_{i=1}^I m_i\pi_i u(c_i)\) is the expected value of \(u(c)\) under a twisted probability distribution \(\{\hat \pi_i\}_{i=1}^I = \{m_i \pi_i\}_{i=1}^I\).

Larger values of the entropy constraint \(\eta\) indicate more apprehension about the baseline probability distribution \(\{\pi_i\}_{i=1}^I\).

Following [Hansen and Sargent, 2001] and [Hansen and Sargent, 2008], we call minimization problem (26.2) subject to (26.3) and(26.4) a constraint problem.

To find minimizing probabilities, we form a Lagrangian

where \(\tilde \theta \geq 0\) is a Lagrange multiplier associated with the entropy constraint.

Subject to the additional constraint that \(\sum_{i=1}^I m_i \pi_i =1\), we want to minimize (26.5) with respect to \(\{m_i\}_{i=1}^I\) and to maximize it with respect to \(\tilde \theta\).

The minimizing probability distortions (likelihood ratios) are

To compute the Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta(c, \eta)\), we must solve

or

for \(\tilde \theta = \tilde \theta(c; \eta)\).

For a fixed \(\eta\), the \(\tilde \theta\) that solves equation (26.7) is evidently a function of the consumption plan \(c\).

With \(\tilde \theta(c;\eta)\) in hand we can obtain worst-case probabilities as functions \(\pi_i\tilde m_i(c;\eta)\) of \(\eta\).

The indirect (expected) utility function under constraint preferences is

Entropy evaluated at the minimizing probability distortion (26.6) equals \(E \tilde m \log \tilde m\) or

Expression (26.9) implies that

where the last term is \(\tilde \theta\) times the entropy of the worst-case probability distribution.

26.6. Multiplier preferences#

A decision maker is said to have multiplier preferences when he ranks consumption plans \(c\) according to

where minimization is subject to

Here \(\theta \in (\underline \theta, +\infty )\) is a ‘penalty parameter’ that governs a ‘cost’ to an ‘evil alter ego’ who distorts probabilities by choosing \(\{m_i\}_{i=1}^I\).

Lower values of the penalty parameter \(\theta\) express more apprehension about the baseline probability distribution \(\pi\).

Following [Hansen and Sargent, 2001] and [Hansen and Sargent, 2008], we call the minimization problem on the right side of (26.11) a multiplier problem.

The minimizing probability distortion that solves the multiplier problem is

We can solve

to find an entropy level \(\tilde \eta (c; \theta)\) associated with multiplier preferences with penalty parameter \(\theta\) and allocation \(c\).

For a fixed \(\theta\), the \(\tilde \eta\) that solves equation (26.13) is a function of the consumption plan \(c\)

The forms of expressions (26.6) and (26.12) are identical, but the Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta\) appears in (26.6), while the penalty parameter \(\theta\) appears in (26.12).

Formulas (26.6) and (26.12) show that worst-case probabilities are context specific in the sense that they depend on both the utility function \(u\) and the consumption plan \(c\).

If we add \(\theta\) times entropy under the worst-case model to expected utility under the worst-case model, we find that the indirect expected utility function under multiplier preferences is

26.7. Risk-sensitive preferences#

Substituting \(\hat m_i\) into \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i \hat m_i [ u(c_i) + \theta \log \hat m_i ]\) gives the indirect utility function

Here \({\sf T} u\) in (26.15) is the risk-sensitivity operator of [Jacobson, 1973], [Whittle, 1981], and [Whittle, 1990].

It defines a risk-sensitive preference ordering over plans \(c\).

Because it is not linear in utilities \(u(c_i)\) and probabilities \(\pi_i\), it is said not to be separable across states.

Because risk-sensitive preferences use a unique probability distribution, they apparently express no model distrust or ambiguity.

Instead, they make an additional adjustment for risk-aversion beyond that embedded in the curvature of \(u\).

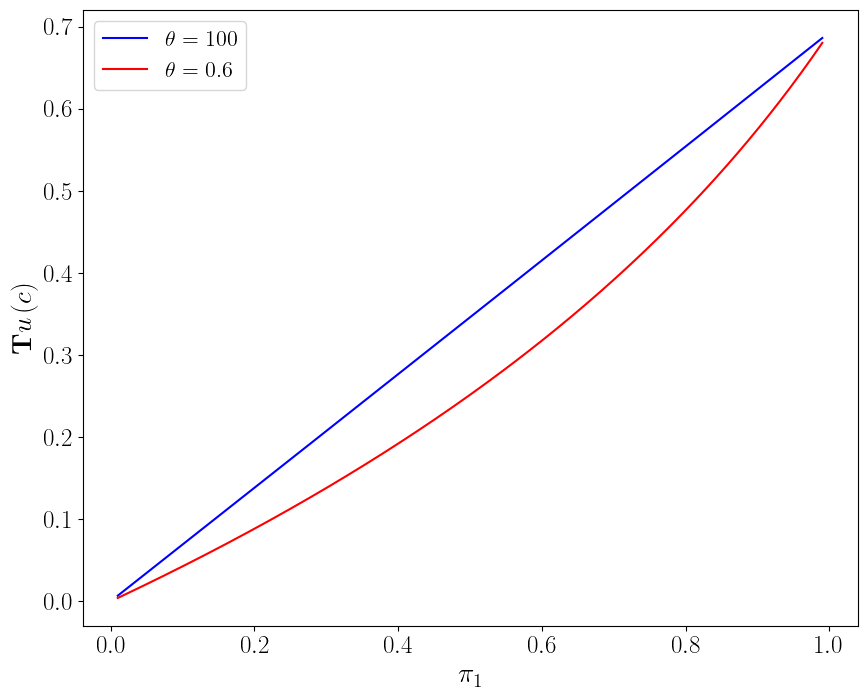

For \(I=2, c_1=2, c_2=1\), \(u(c) = \ln c\), the following figure plots the risk-sensitive criterion \({\sf T} u(c)\) defined in (26.15) as a function of \(\pi_1\) for values of \(\theta\) of 100 and .6.

For large values of \(\theta\), \({\sf T} u(c)\) is approximately linear in the probability \(\pi_1\), but for lower values of \(\theta\), \({\sf T} u(c)\) has considerable curvature as a function of \(\pi_1\).

Under expected utility, i.e., \(\theta =+\infty\), \({\sf T}u(c)\) is linear in \(\pi_1\), but it is convex as a function of \(\pi_1\) when \(\theta< + \infty\).

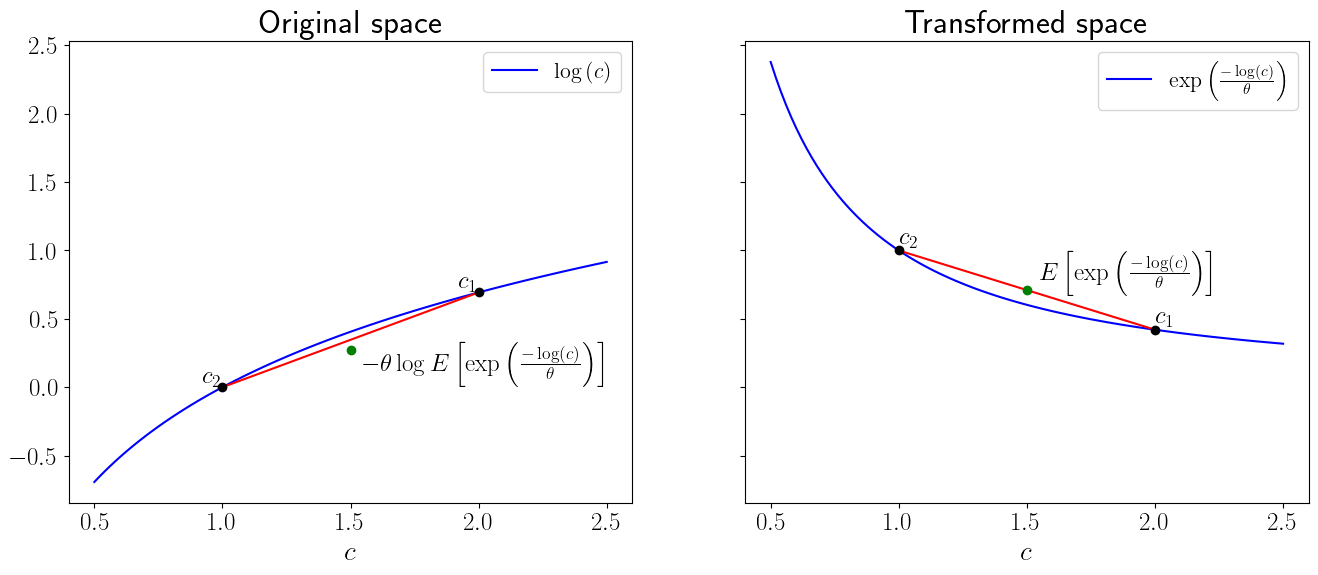

The two panels in the next figure below can help us to visualize the extra adjustment for risk that the risk-sensitive operator entails.

This will help us understand how the \(\sf{T}\) transformation works by envisioning what function is being averaged.

The panel on the right portrays how the transformation \(\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c\right)}{\theta}\right)\) sends \(u\left(c\right)\) to a new function by (i) flipping the sign, and (ii) increasing curvature in proportion to \(\theta\).

In the left panel, the red line is our tool for computing the mathematical expectation for different values of \(\pi\).

The green lot indicates the mathematical expectation of \(\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c\right)}{\theta}\right)\) when \(\pi = .5\).

Notice that the distance between the green dot and the curve is greater in the transformed space than the original space as a result of additional curvature.

The inverse transformation \(\theta\log E\left[\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c\right)}{\theta}\right)\right]\) generates the green dot on the left panel that constitutes the risk-sensitive utility index.

The gap between the green dot and the red line on the left panel measures the additional adjustment for risk that risk-sensitive preferences make relative to plain vanilla expected utility preferences.

26.7.1. Digression on moment generating functions#

The risk-sensitivity operator \({\sf T}\) is intimately connected to a moment generating function.

In particular, a principal constinuent of the \({\sf T}\) operator, namely,

is evidently a moment generating function for the random variable \(u(c_i)\), while

is a cumulant generating function,

where \(\kappa_j\) is the \(j\)th cumulant of the random variable \(u(c)\).

Then

In general, when \(\theta < +\infty\), \({\sf T} u(c)\) depends on cumulants of all orders.

These statements extend to cases with continuous probability distributions for \(c\) and therefore for \(u(c)\).

For the special case \(u(c) \sim {\mathcal N}(\mu_u, \sigma_u^2)\), \(\kappa_1 = \mu_u, \kappa_2 = \sigma_u^2,\) and \(\kappa_j = 0 \ \forall j \geq 3\), so

which becomes expected utility \(\mu_u\) when \(\theta^{-1} = 0\).

The right side of equation (26.16) is a special case of stochastic differential utility preferences in which consumption plans are ranked not just by their expected utilities \(\mu_u\) but also the variances \(\sigma_u^2\) of their expected utilities.

26.8. Ex post Bayesian preferences#

A decision maker is said to have ex post Bayesian preferences when he ranks consumption plans according to the expected utility function

where \(\hat \pi(c^*)\) is the worst-case probability distribution associated with multiplier or constraint preferences evaluated at a particular consumption plan \(c^* = \{c_i^*\}_{i=1}^I\).

At \(c^*\), an ex post Bayesian’s indifference curves are tangent to those for multiplier and constraint preferences with appropriately chosen \(\theta\) and \(\eta\), respectively.

26.9. Comparing preferences#

For the special case in which \(I=2\), \(c_1=2, c_2=1\), \(u(c) = \ln c\), and \(\pi_1 =.5\), the following two figures depict how worst-case probabilities are determined under constraint and multiplier preferences, respectively.

The first figure graphs entropy as a function of \(\hat \pi_1\).

It also plots expected utility under the twisted probability distribution, namely, \(\hat E u(c) = u(c_2) + \hat \pi_1 (u(c_1) - u(c_2))\), which is evidently a linear function of \(\hat \pi_1\).

The entropy constraint \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i m_i \log m_i \leq \eta\) implies a convex set \(\hat \Pi_1\) of \(\hat \pi_1\)’s that constrains the adversary who chooses \(\hat \pi_1\), namely, the set of \(\hat \pi_1\)’s for which the entropy curve lies below the horizontal dotted line at an entropy level of \(\eta = .25\).

Unless \(u(c_1) = u(c_2)\), the \(\hat \pi_1\) that minimizes \(\hat E u(c)\) is at the boundary of the set \(\hat \Pi_1\).

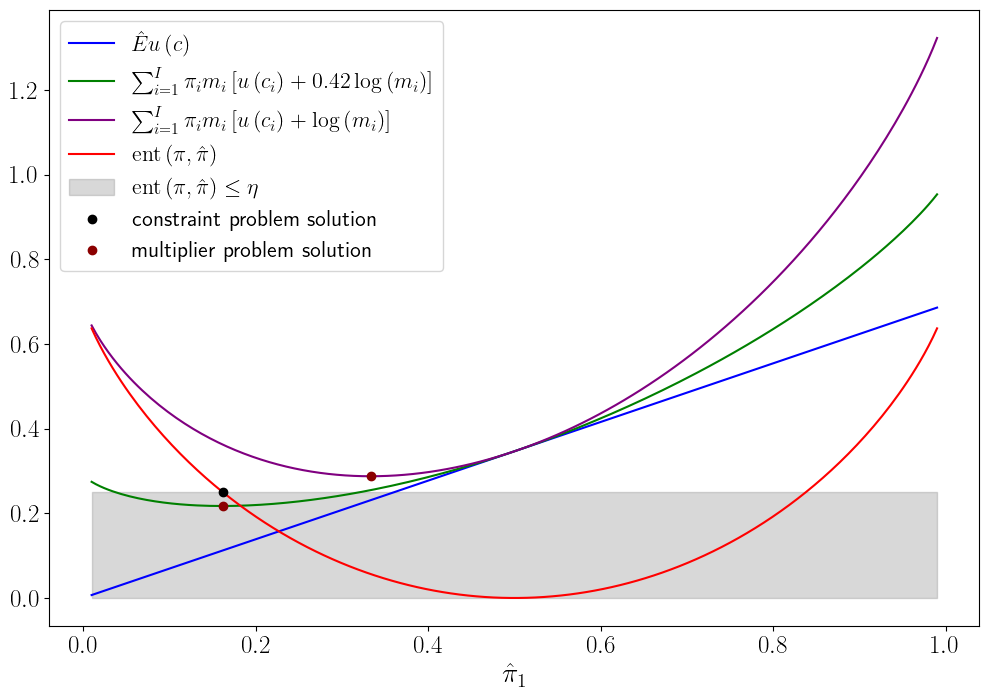

The next figure shows the function \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i m_i [ u(c_i) + \theta \log m_i ]\) that is to be minimized in the multiplier problem.

The argument of the function is \(\hat \pi_1 = m_1 \pi_1\).

Evidently, from this figure and also from formula (26.12), lower values of \(\theta\) lead to lower, and thus more distorted, minimizing values of \(\hat \pi_1\).

The figure indicates how one can construct a Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta\) associated with a given entropy constraint \(\eta\) and a given consumption plan.

Thus, to draw the figure, we set the penalty parameter for multiplier preferences \(\theta\) so that the minimizing \(\hat \pi_1\) equals the minimizing \(\hat \pi_1\) for the constraint problem from the previous figure.

The penalty parameter \(\theta=.42\) also equals the Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta\) on the entropy constraint for the constraint preferences depicted in the previous figure because the \(\hat \pi_1\) that minimizes the asymmetric curve associated with penalty parameter \(\theta=.42\) is the same \(\hat \pi_1\) associated with the intersection of the entropy curve and the entropy constraint dashed vertical line.

26.10. Risk aversion and misspecification aversion#

All five types of preferences use curvature of \(u\) to express risk aversion.

Constraint preferences express concern about misspecification or ambiguity for short with a positive \(\eta\) that circumscribes an entropy ball around an approximating probability distribution \(\pi\), and aversion to model misspecification through minimization with respect to a likelihood ratio \(m\).

Multiplier preferences express misspecification concerns with a parameter \(\theta<+\infty\) that penalizes deviations from the approximating model as measured by relative entropy, and they express aversion to misspecification concerns with minimization over a probability distortion \(m\).

By penalizing minimization over the likelihood ratio \(m\), a decrease in \(\theta\) represents an increase in ambiguity (or what [Knight, 1921] called uncertainty) about the specification of the baseline approximating model \(\{\pi_i\}_{i=1}^I\).

Formulas (26.6) assert that the decision maker acts as if he is pessimistic relative to an approximating model \(\pi\).

It expresses what [Bucklew, 2004] [p. 27] calls a statistical version of Murphy’s law:

\(\quad \quad\) The probability of anything happening is in inverse ratio to its desirability.

The minimizing likelihood ratio \(\hat m\) slants worst-case probabilities \(\hat \pi\) exponentially to increase probabilities of events that give lower utilities.

As expressed by the value function bound (26.19) to be displayed below, the decision maker uses pessimism instrumentally to protect himself against model misspecification.

The penalty parameter \(\theta\) for multipler preferences or the entropy level \(\eta\) that determines the Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta\) for constraint preferences controls how adversely the decision maker exponentially slants probabilities.

A decision rule is said to be undominated in the sense of Bayesian decision theory if there exists a probability distribution \(\pi\) for which it is optimal.

A decision rule is said to be admissible if it is undominated.

[Hansen and Sargent, 2008] use ex post Bayesian preferences to show that robust decision rules are undominated and therefore admissible.

26.11. Indifference curves#

Indifference curves illuminate how concerns about robustness affect asset pricing and utility costs of fluctuations. For \(I=2\), the slopes of the indifference curves for our five preference specifications are

Expected utility:

\[ \frac{d c_2}{d c_1} = - \frac{\pi_1}{\pi_2}\frac{u'(c_1)}{u'(c_2)} \]Constraint and ex post Bayesian preferences:

\[ \frac{d c_2}{d c_1} = - \frac{\hat \pi_1}{\hat \pi_2}\frac{u'(c_1)}{u'(c_2)} \]where \(\hat \pi_1, \hat \pi_2\) are the minimizing probabilities computed from the worst-case distortions (26.6) from the constraint problem at \((c_1, c_2)\).

Multiplier and risk-sensitive preferences:

\[ \frac{d c_2}{d c_1} = - \frac{\pi_1}{\pi_2} \frac{\exp(- u(c_1)/\theta)}{\exp (- u(c_2)/\theta)} \frac{u'(c_1)}{u'(c_2)} \]

When \(c_1 > c_2\), the exponential twisting formula (26.12) implies that \(\hat \pi_1 < \pi_1\), which in turn implies that the indifference curves through \((c_1, c_2)\) for both constraint and multiplier preferences are flatter than the indifference curve associated with expected utility preferences.

As we shall see soon when we discuss state price deflators, this gives rise to higher estimates of prices of risk.

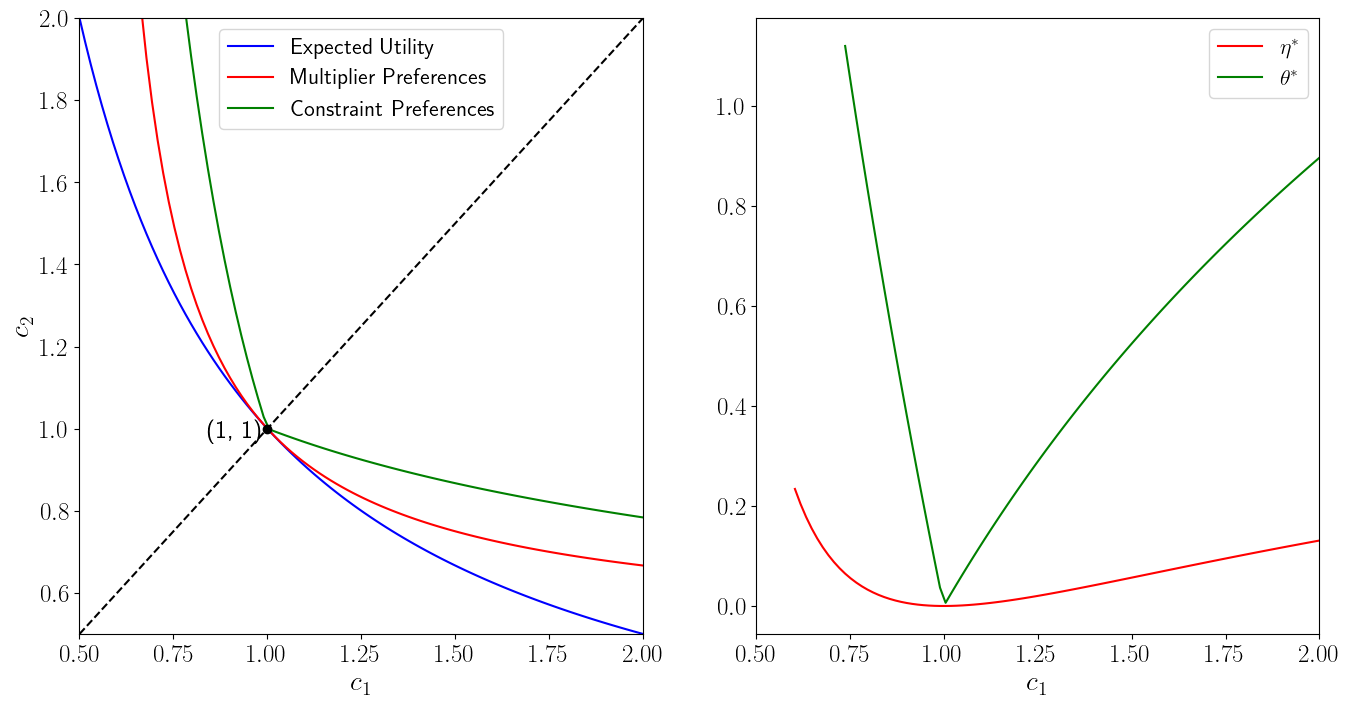

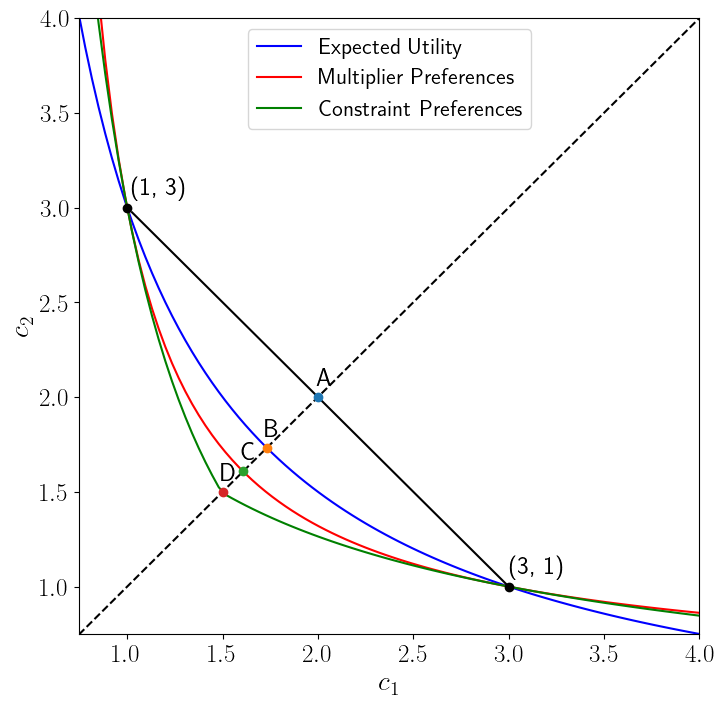

For an example with \(u(c) = \ln c\), \(I=2\), and \(\pi_1 = .5\), the next two figures show indifference curves for expected utility, multiplier, and constraint preferences.

The following figure shows indifference curves going through a point along the 45 degree line.

Kink at 45 degree line

Notice the kink in the indifference curve for constraint preferences at the 45 degree line.

To understand the source of the kink, consider how the Lagrange multiplier and worst-case probabilities vary with the consumption plan under constraint preferences.

For fixed \(\eta\), a given plan \(c\), and a utility function increasing in \(c\), worst case probabilities are fixed numbers \(\hat \pi_1 < .5\) when \(c_1 > c_2\) and \(\hat \pi_1 > .5\) when \(c_2 > c_1\).

This pattern makes the Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta\) vary discontinuously at \(\hat \pi_1 = .5\).

The discontinuity in the worst case \(\hat \pi_1\) at the 45 degree line accounts for the kink at the 45 degree line in an indifference curve for constraint preferences associated with a given positive entropy constraint \(\eta\).

The code for generating the preceding figure is somewhat intricate we formulate a root finding problem for finding indifference curves.

Here is a brief literary description of the method we use.

Parameters

Consumption bundle \(c=\left(1,1\right)\)

Penalty parameter \(θ=2\)

Utility function \(u=\log\)

Probability vector \(\pi=\left(0.5,0.5\right)\)

Algorithm:

Compute \(\bar{u}=\pi_{1}u\left(c_{1}\right)+\pi_{2}u\left(c_{2}\right)\)

Given values for \(c_{1}\), solve for values of \(c_{2}\) such that \(\bar{u}=u\left(c_{1},c_{2}\right)\):

Expected utility: \(c_{2,EU}=u^{-1}\left(\frac{\bar{u}-\pi_{1}u\left(c_{1}\right)}{\pi_{2}}\right)\)

Multiplier preferences: solve \(\bar{u}-\sum_{i}\pi_{i}\frac{\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{i}\right)}{\theta}\right)}{\sum_{j}\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{j}\right)}{\theta}\right)}\left(u\left(c_{i}\right)+\theta\log\left(\frac{\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{i}\right)}{\theta}\right)}{\sum_{j}\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{j}\right)}{\theta}\right)}\right)\right)=0\) numerically

Constraint preference: solve \(\bar{u}-\sum_{i}\pi_{i}\frac{\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{i}\right)}{\theta^{*}}\right)}{\sum_{j}\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{j}\right)}{\theta^{*}}\right)}u\left(c_{i}\right)=0\) numerically where \(\theta^{*}\) solves \(\sum_{i}\pi_{i}\frac{\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{i}\right)}{\theta^{*}}\right)}{\sum_{j}\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{j}\right)}{\theta^{*}}\right)}\log\left(\frac{\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{i}\right)}{\theta^{*}}\right)}{\sum_{j}\exp\left(\frac{-u\left(c_{j}\right)}{\theta^{*}}\right)}\right)-\eta=0\) numerically.

Remark: It seems that the constraint problem is hard to solve in its original form, i.e. by finding the distorting measure that minimizes the expected utility.

It seems that viewing equation (26.7) as a root finding problem works much better.

But notice that equation (26.7) does not always have a solution.

Under \(u=\log\), \(c_{1}=c_{2}=1\), we have:

Conjecture: when our numerical method fails it because the derivative of the objective doesn’t exist for our choice of parameters.

Remark: It is tricky to get the algorithm to work properly for all values of \(c_{1}\). In particular, parameters were chosen with graduate student descent.

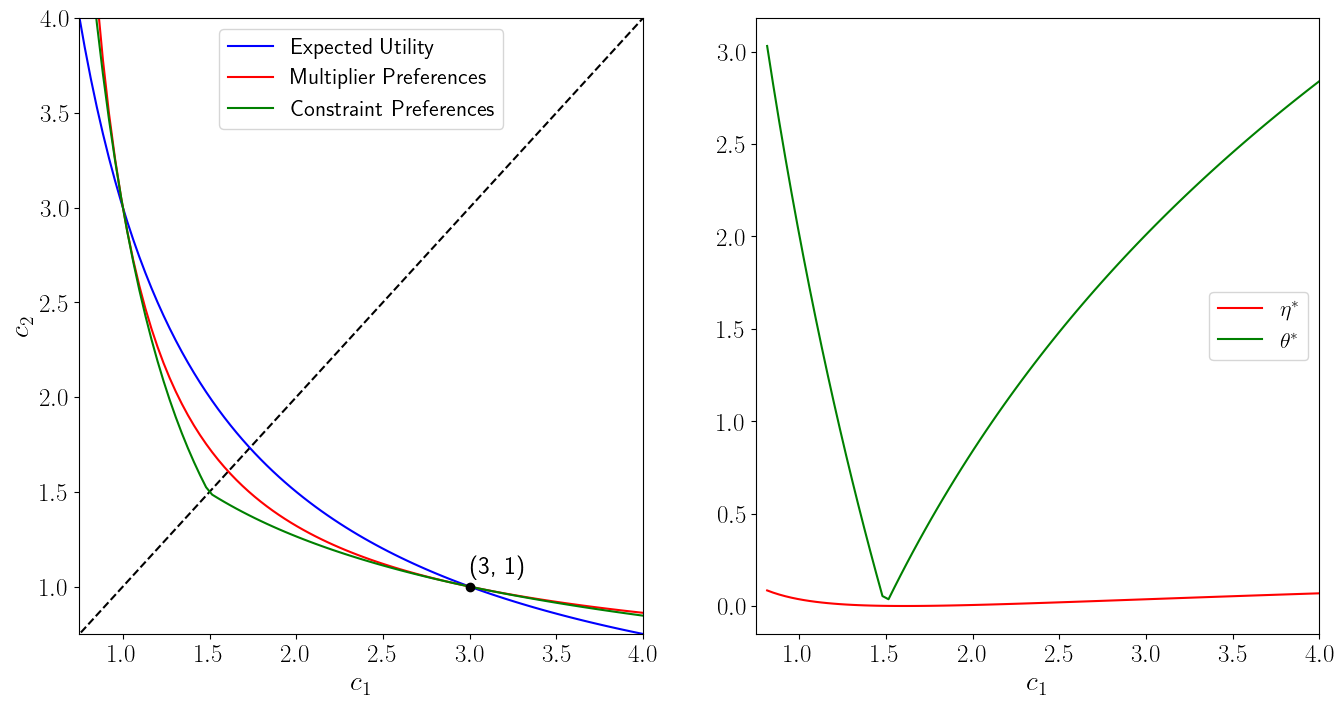

Tangent indifference curves off 45 degree line

For a given \(\eta\) and a given allocation \((c_1, c_2)\) off the 45 degree line, by solving equations (26.7) and (26.13), we can find \(\tilde \theta (\eta, c)\) and \(\tilde \eta(\theta,c)\) that make indifference curves for multiplier and constraint preferences be tangent to one another.

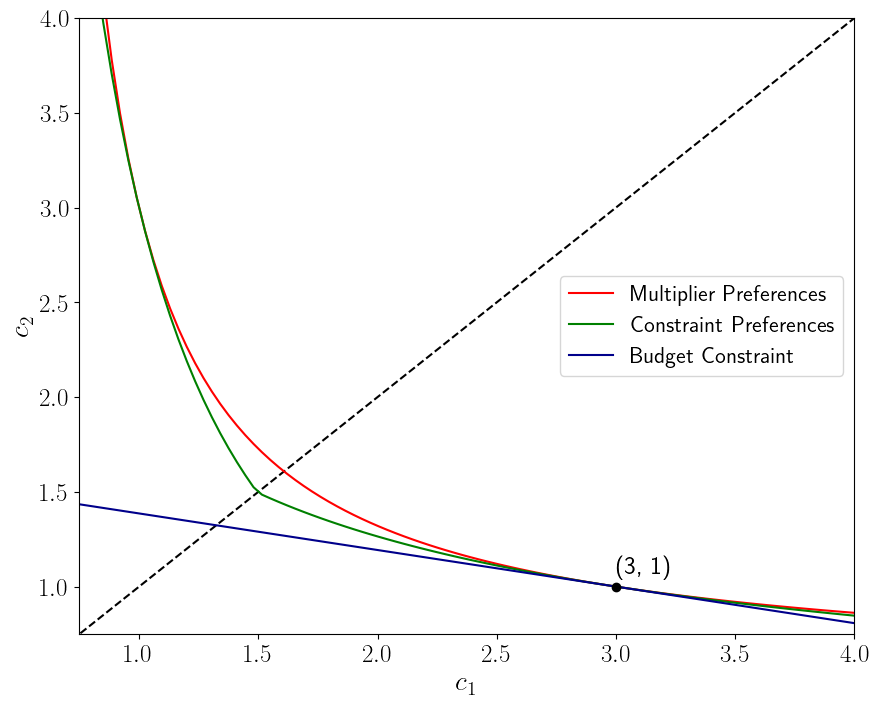

The following figure shows indifference curves for multiplier and constraint preferences through a point off the 45 degree line, namely, \((c(1),c(2)) = (3,1)\), at which \(\eta\) and \(\theta\) are adjusted to render the indifference curves for constraint and multiplier preferences tangent.

Note that all three lines of the left graph intersect at (1, 3). While the intersection at (3, 1) is hard-coded, the intersection at (1,3) arises from the computation, which confirms that the code seems to be working properly.

As we move along the (kinked) indifference curve for the constraint preferences for a given \(\eta\), the worst-case probabilities remain constant, but the Lagrange multiplier \(\tilde \theta\) on the entropy constraint \(\sum_{i=1}^I m_i \log m_i \leq \eta\) varies with \((c_1, c_2)\).

As we move along the (smooth) indifference curve for the multiplier preferences for a given penalty parameter \(\theta\), the implied entropy \(\tilde \eta\) from equation (26.13) and the worst-case probabilities both change with \((c_1, c_2)\).

For constraint preferences, there is a kink in the indifference curve.

For ex post Bayesian preferences, there are effectively two sets of indifference curves depending on which side of the 45 degree line the \((c_1, c_2)\) endowment point sits.

There are two sets of indifference curves because, while the worst-case probabilities differ above and below the 45 degree line, the idea of ex post Bayesian preferences is to use a single probability distribution to compute expected utilities for all consumption bundles.

Indifference curves through point \((c_1, c_2) = (3,1)\) for expected logarithmic utility (less curved smooth line), multiplier (more curved line), constraint (solid line kinked at 45 degree line), and ex post Bayesian (dotted lines) preferences. The worst-case probability \(\hat \pi_1 < .5\) when \(c_1 =3 > c_2 =1\) and \(\hat \pi_1 > .5\) when \(c_1=1 < c_2 = 3\).

26.12. State price deflators#

Concerns about model uncertainty boost prices of risk that are embedded in state-price deflators. With complete markets, let \(q_i\) be the price of consumption in state \(i\).

The budget set of a representative consumer having endowment \(\bar c = \{\bar c_i\}_{i=1}^I\) is expressed by \(\sum_{i}^I q_i (c_i - \bar c_i) \leq 0\).

When a representative consumer has multiplier preferences, the state prices are

The worst-case likelihood ratio \(\hat m_i\) operates to increase prices \(q_i\) in relatively low utility states \(i\).

State prices agree under multiplier and constraint preferences when \(\eta\) and \(\theta\) are adjusted according to (26.7) or (26.13) to make the indifference curves tangent at the endowment point.

The next figure can help us think about state-price deflators under our different preference orderings.

In this figure, budget line and indifference curves through point \((c_1, c_2) = (3,1)\) for expected logarithmic utility, multiplier, constraint (kinked at 45 degree line), and ex post Bayesian (dotted lines) preferences.

Figure 2.7:

Because budget constraints are linear, asset prices are identical under multiplier and constraint preferences for which \(\theta\) and \(\eta\) are adjusted to verify (26.7) or (26.13) at a given consumption endowment \(\{c_i\}_{i=1}^I\).

However, as we note next, though they are tangent at the endowment point, the fact that indifference curves differ for multiplier and constraint preferences means that certainty equivalent consumption compensations of the kind that [Lucas, 1987], [Hansen et al., 1999], [Tallarini, 2000], and [Barillas et al., 2009] used to measure the costs of business cycles must differ.

26.12.1. Consumption-equivalent measures of uncertainty aversion#

For each of our five types of preferences, the following figure allows us to construct a certainty equivalent point \((c^*, c^*)\) on the 45 degree line that renders the consumer indifferent between it and the risky point \((c(1), c(2)) = (3,1)\).

Figure 2.8:

The figure indicates that the certainty equivalent level \(c^*\) is higher for the consumer with expected utility preferences than for the consumer with multiplier preferences, and that it is higher for the consumer with multiplier preferences than for the consumer with constraint preferences.

The gap between these certainty equivalents measures the uncertainty aversion of the multiplier preferences or constraint preferences consumer.

The gap between the expected value \(.5 c(1) + .5 c(2)\) at point A and the certainty equivalent for the expected utility decision maker at point B is a measure of his risk aversion.

The gap between points \(B\) and \(C\) measures the multiplier preference consumer’s aversion to model uncertainty.

The gap between points B and D measures the constraint preference consumer’s aversion to model uncertainty.

26.13. Iso-utility and iso-entropy curves and expansion paths#

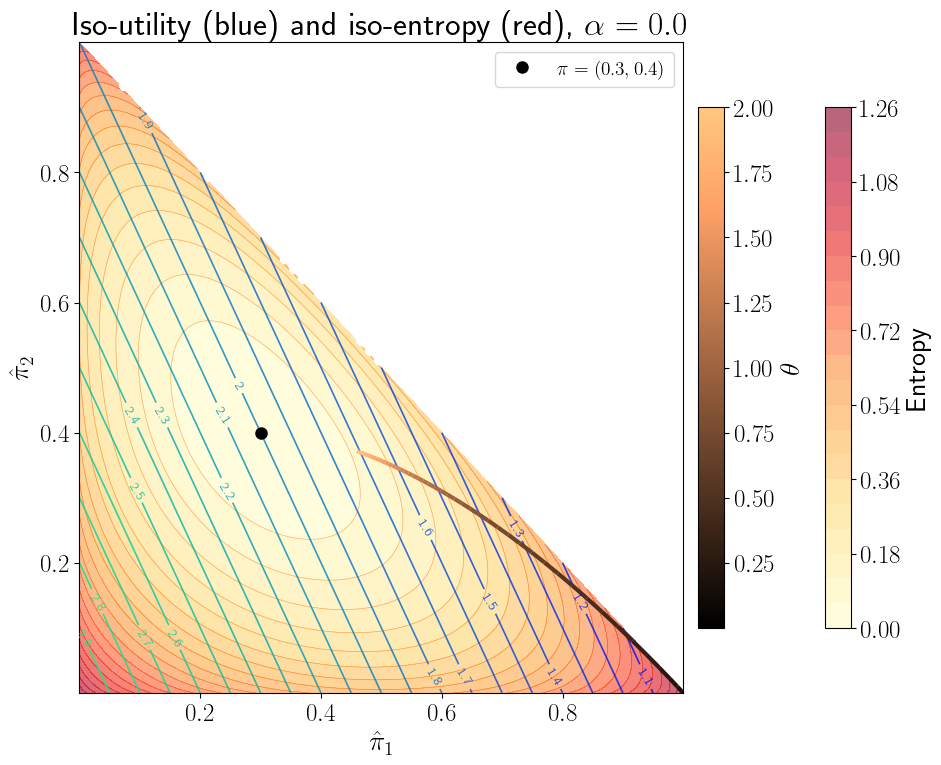

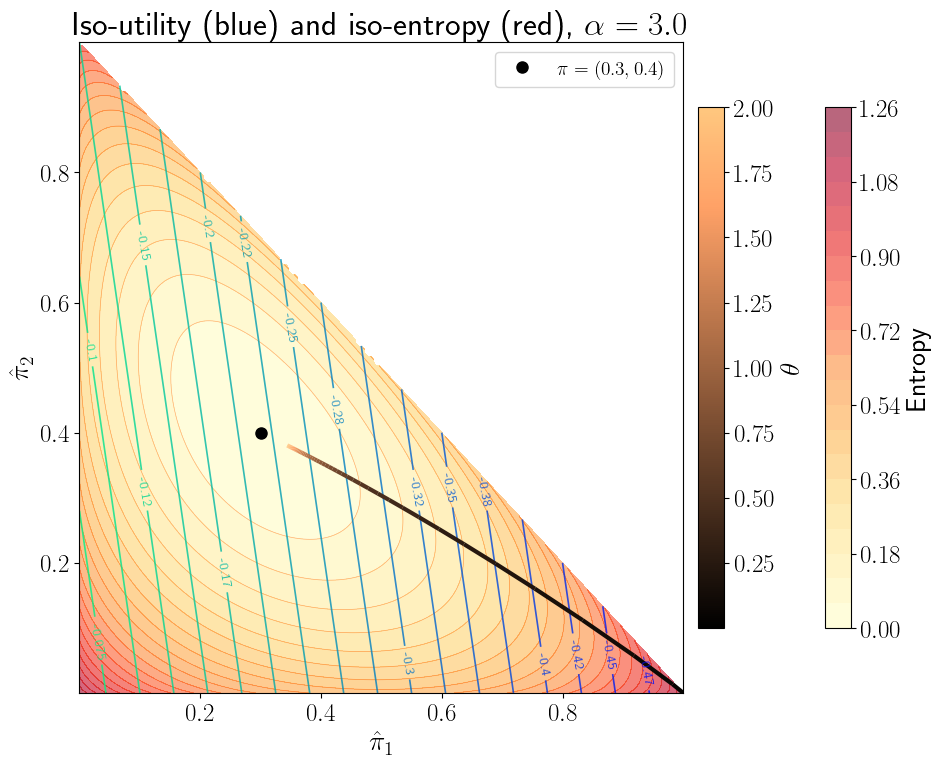

The following figures show iso-entropy and iso-utility lines for the special case in which \(I = 3\), \(\pi_1 = .3, \pi_2 = .4\), and the utility function is \(u(c)= \frac{c^{1-\alpha}}{1-\alpha}\) with \(\alpha =0\) and \(\alpha =3\), respectively, for the fixed plan \(c(1) = 1, c(2) =2 , c(3) =3\).

The iso-utility lines are the level curves of

and are linear in \((\hat \pi_1, \hat \pi_2)\).

This is what it means to say ‘expected utility is linear in probabilities.’

Both figures plot the locus of points of tangency between the iso-entropy and the iso-utility curves that is traced out as one varies \(\theta^{-1}\) in the interval \([0, 2]\).

While the iso-entropy lines are identical in the two figures, these ‘expansion paths’ differ because the utility functions differ, meaning that for a given \(\theta\) and \((c_1, c_2, c_3)\) triple, the worst-case probabilities \(\hat \pi_i(\theta) = \pi_i \frac{\exp(-u(c_i)/\theta )} {E\exp(-u(c)/\theta )}\) differ as we vary \(\theta\), causing the associated entropies to differ.

26.14. Bounds on expected utility#

Suppose that a decision maker wants a lower bound on expected utility \(\sum_{i=1}^I \hat \pi_i u(c_i)\) that is satisfied for any distribution \(\hat \pi\) with relative entropy less than or equal to \(\eta\).

An attractive feature of multiplier and constraint preferences is that they carry with them such a bound.

To show this, it is useful to collect some findings in the following string of inequalities associated with multiplier preferences:

where \(m_i^* \propto \exp \Bigl( \frac{- u(c_i)}{\theta} \Bigr)\) are the worst-case distortions to probabilities.

The inequality in the last line just asserts that minimizers minimize.

Therefore, we have the following useful bound:

The left side is expected utility under the probability distribution \(\{ m_i \pi_i\}\).

The right side is a lower bound on expected utility under all distributions expressed as an affine function of relative entropy \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i m_i \log m_i\).

The bound is attained for \(m_i = m_i^* \propto \exp \Bigl(\frac{- u (c_i)}{\theta} \Bigr)\).

The intercept in the bound is the risk-sensitive criterion \({\sf T}_\theta u(c)\), while the slope is the penalty parameter \(\theta\).

Lowering \(\theta\) does two things:

it lowers the intercept \({\sf T}_\theta u(c)\), which makes the bound less informative for small values of entropy; and

it lowers the absolute value of the slope, which makes the bound more informative for larger values of relative entropy \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i m_i \log m_i\).

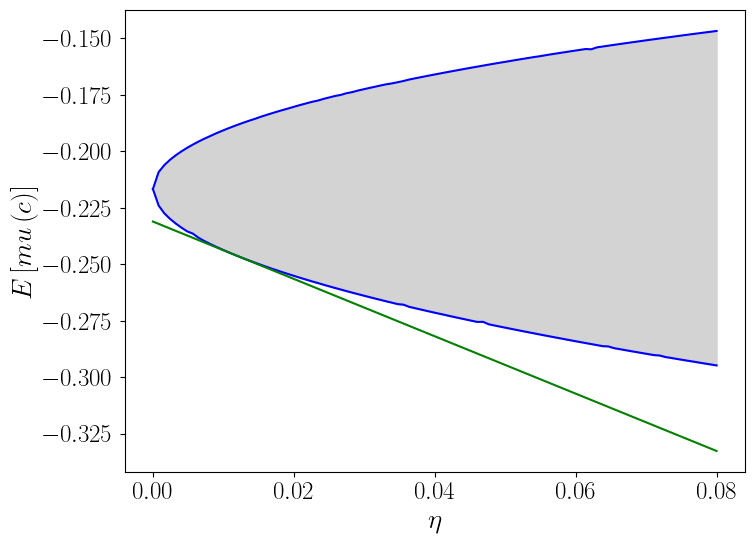

The following figure reports best-case and worst-case expected utilities.

We calculate the lines in this figure numerically by solving optimization problems with respect to the change of measure.

In this figure, expected utility is on the co-ordinate axis while entropy is on the ordinate axis.

The lower curved line depicts expected utility under the worst-case model associated with each value of entropy \(\eta\) recorded on the ordinate axis, i.e., it is \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i \tilde m_i (\tilde \theta(c,\eta)) u(c_i)\), where \(\tilde m_i (\tilde \theta(\eta)) \propto \exp \Bigl(\frac{-u(c_i)}{\tilde \theta}\Bigr)\) and \(\tilde \theta\) is the Lagrange multiplier associated with the constraint that entropy cannot exceed the value on the ordinate axis.

The higher curved line depicts expected utility under the best-case model indexed by the value of the Lagrange multiplier \(\check \theta >0\) associated with each value of entropy less than or equal to \(\eta\) recorded on the ordinate axis, i.e., it is \(\sum_{i=1}^I \pi_i \check m_i (\check \theta(\eta)) u(c_i)\) where \(\check m_i (\check \theta(c,\eta)) \propto \exp \Bigl(\frac{u(c_i)}{\check \theta}\Bigr)\).

(Here \(\check \theta\) is the Lagrange multiplier associated with max-max expected utility.)

Points between these two curves are possible values of expected utility for some distribution with entropy less than or equal to the value \(\eta\) on the ordinate axis.

The straight line depicts the right side of inequality (26.19) for a particular value of the penalty parameter \(\theta\).

As noted, when one lowers \(\theta\), the intercept \({\sf T}_\theta u(c)\) and the absolute value of the slope both decrease.

Thus, as \(\theta\) is lowered, \({\sf T}_\theta u(c)\) becomes a more conservative estimate of expected utility under the approximating model \(\pi\).

However, as \(\theta\) is lowered, the robustness bound (26.19) becomes more informative for sufficiently large values of entropy.

The slope of straight line depicting a bound is \(-\theta\) and the projection of the point of tangency with the curved depicting the lower bound of expected utility is the entropy associated with that \(\theta\) when it is interpreted as a Lagrange multiplier on the entropy constraint in the constraint problem .

This is an application of the envelope theorem.

26.15. Why entropy?#

Beyond the helpful mathematical fact that it leads directly to convenient exponential twisting formulas (26.6) and (26.12) for worst-case probability distortions, there are two related justifications for using entropy to measure discrepancies between probability distribution.

One arises from the role of entropy in statistical tests for discriminating between models.

The other comes from axioms.

26.15.1. Entropy and statistical detection#

Robust control theory starts with a decision maker who has constructed a good baseline approximating model whose free parameters he has estimated to fit historical data well.

The decision maker recognizes that actual outcomes might be generated by one of a vast number of other models that fit the historical data nearly as well as his.

Therefore, he wants to evaluate outcomes under a set of alternative models that are plausible in the sense of being statistically close to his model.

He uses relative entropy to quantify what close means.

[Anderson et al., 2003] and [Barillas et al., 2009]describe links between entropy and large deviations bounds on test statistics for discriminating between models, in particular, statistics that describe the probability of making an error in applying a likelihood ratio test to decide whether model A or model B generated a data record of length \(T\).

For a given sample size, an informative bound on the detection error probability is a function of the entropy parameter \(\eta\) in constraint preferences. [Anderson et al., 2003] and [Barillas et al., 2009] use detection error probabilities to calibrate reasonable values of \(\eta\).

[Anderson et al., 2003] and [Hansen and Sargent, 2008] also use detection error probabilities to calibrate reasonable values of the penalty parameter \(\theta\) in multiplier preferences.

For a fixed sample size and a fixed \(\theta\), they would calculate the worst-case \(\hat m_i(\theta)\), an associated entropy \(\eta(\theta)\), and an associated detection error probability. In this way they build up a detection error probability as a function of \(\theta\).

They then invert this function to calibrate \(\theta\) to deliver a reasonable detection error probability.

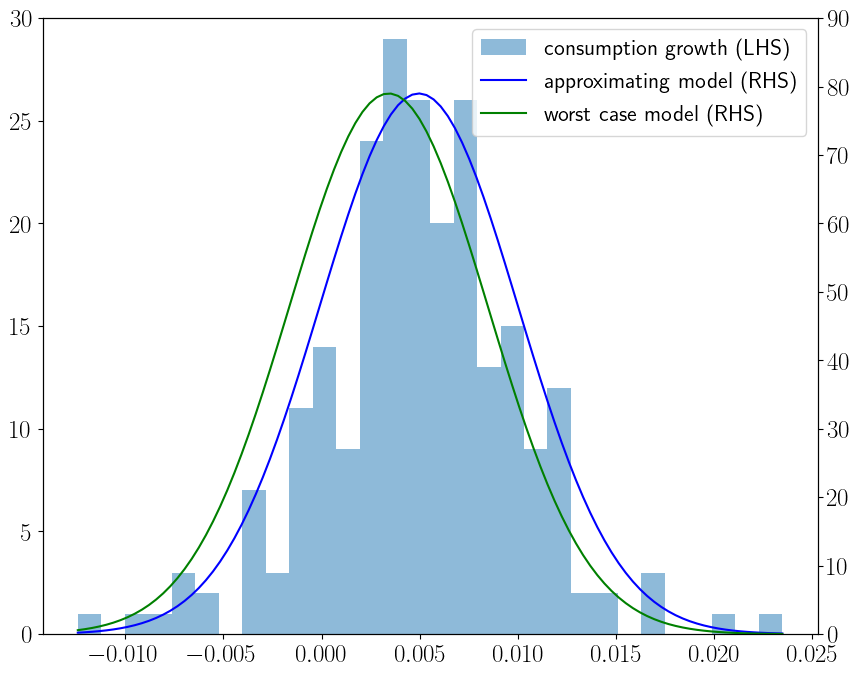

To indicate outcomes from this approach, the following figure plots the histogram for U.S. quarterly consumption growth along with a representative agent’s approximating density and a worst-case density that [Barillas et al., 2009] show imply high measured market prices of risk even when a representative consumer has the unit coefficient of relative risk aversion associated with a logarithmic one-period utility function.

The density for the approximating model is \(\log c_{t+1} - \log c_t = \mu + \sigma_c \epsilon_{t+1}\) where \(\epsilon_{t+1} \sim {\cal N}(0,1)\) and \(\mu\) and \(\sigma_c\) are estimated by maximum likelihood from the U.S. quarterly data in the histogram over the period 1948.I-2006.IV.

The consumer’s value function under logarithmic utility implies that the worst-case model is \(\log c_{t+1} - \log c_t = (\mu + \sigma_c w) + \sigma_c \tilde \epsilon_{t+1}\) where \(\{\tilde \epsilon_{t+1}\}\) is also a normalized Gaussian random sequence and where \(w\) is calculated by setting a detection error probability to \(.05\).

The worst-case model appears to fit the histogram nearly as well as the approximating model.

26.15.2. Axiomatic justifications#

Multiplier and constraint preferences are both special cases of what [Maccheroni et al., 2006] call variational preferences.

They provide an axiomatic foundation for variational preferences and describe how they express ambiguity aversion.

Constraint preferences are particular instances of the multiple priors model of [Gilboa and Schmeidler, 1989].