18. Growth in Dynamic Linear Economies#

This is another member of a suite of lectures that use the quantecon DLE class to instantiate models within the [Hansen and Sargent, 2013] class of models described in detail in Recursive Models of Dynamic Linear Economies.

In addition to what’s included in Anaconda, this lecture uses the quantecon library.

!pip install --upgrade quantecon

This lecture describes several complete market economies having a common linear-quadratic-Gaussian structure.

Three examples of such economies show how the DLE class can be used to compute equilibria of such economies in Python and to illustrate how different versions of these economies can or cannot generate sustained growth.

We require the following imports

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from quantecon import DLE

18.1. Common structure#

Our example economies have the following features

Information flows are governed by an exogenous stochastic process \(z_t\) that follows

\[ z_{t+1} = A_{22}z_t + C_2w_{t+1} \]where \(w_{t+1}\) is a martingale difference sequence.

Preference shocks \(b_t\) and technology shocks \(d_t\) are linear functions of \(z_t\)

\[ b_t = U_bz_t \]\[ d_t = U_dz_t \]Consumption and physical investment goods are produced using the following technology

\[ \Phi_c c_t + \Phi_g g_t + \Phi_i i_t = \Gamma k_{t-1} + d_t \]\[ k_t = \Delta_k k_{t-1} + \Theta_k i_t \]\[ g_t \cdot g_t = l_t^2 \]where \(c_t\) is a vector of consumption goods, \(g_t\) is a vector of intermediate goods, \(i_t\) is a vector of investment goods, \(k_t\) is a vector of physical capital goods, and \(l_t\) is the amount of labor supplied by the representative household.

Preferences of a representative household are described by

\[ -\frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}\sum_{t=0}^\infty \beta^t [(s_t-b_t)\cdot(s_t - b_t) + l_t^2], 0 < \beta < 1 \]\[ s_t = \Lambda h_{t-1} + \Pi c_t \]\[ h_t = \Delta_h h_{t-1} + \Theta_h c_t \]

where \(s_t\) is a vector of consumption services, and \(h_t\) is a vector of household capital stocks.

Thus, an instance of this class of economies is described by the matrices

and the scalar \(\beta\).

18.2. A planning problem#

The first welfare theorem asserts that a competitive equilibrium allocation solves the following planning problem.

Choose \(\{c_t, s_t, i_t, h_t, k_t, g_t\}_{t=0}^\infty\) to maximize

subject to the linear constraints

and

The DLE class in Python maps this planning problem into a linear-quadratic dynamic programming problem and then solves it by using QuantEcon’s LQ class.

(See Section 5.5 of Hansen & Sargent (2013) [Hansen and Sargent, 2013] for a full description of how to map these economies into an LQ setting, and how to use the solution to the LQ problem to construct the output matrices in order to simulate the economies)

The state for the LQ problem is

and the control variable is \(u_t = i_t\).

Once the LQ problem has been solved, the law of motion for the state is

where the optimal control law is \(u_t = -Fx_t\).

Letting \(A^o = A-BF\) we write this law of motion as

18.3. Example economies#

Each of the example economies shown here will share a number of components. In particular, for each we will consider preferences of the form

Technology of the form

And information of the form

We shall vary \(\{\lambda, \pi, \delta_h, \theta_h, \gamma_1, \delta_k, \phi_1\}\) and the initial state \(x_0\) across the three economies.

18.3.1. Example 1: Hall (1978)#

First, we set parameters such that consumption follows a random walk. In particular, we set

(In this economy \(\delta_h\) and \(\theta_h\) are arbitrary as household capital does not enter the equation for consumption services We set them to values that will become useful in Example 3)

It is worth noting that this choice of parameter values ensures that \(\beta(\gamma_1 + \delta_k) = 1\).

For simulations of this economy, we choose an initial condition of

# Parameter Matrices

γ_1 = 0.1

ϕ_1 = 1e-5

ϕ_c, ϕ_g, ϕ_i, γ, δ_k, θ_k = (np.array([[1], [0]]),

np.array([[0], [1]]),

np.array([[1], [-ϕ_1]]),

np.array([[γ_1], [0]]),

np.array([[.95]]),

np.array([[1]]))

β, l_λ, π_h, δ_h, θ_h = (np.array([[1 / 1.05]]),

np.array([[0]]),

np.array([[1]]),

np.array([[.9]]),

np.array([[1]]) - np.array([[.9]]))

a22, c2, ub, ud = (np.array([[1, 0, 0],

[0, 0.8, 0],

[0, 0, 0.5]]),

np.array([[0, 0],

[1, 0],

[0, 1]]),

np.array([[30, 0, 0]]),

np.array([[5, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0]]))

# Initial condition

x0 = np.array([[5], [150], [1], [0], [0]])

info1 = (a22, c2, ub, ud)

tech1 = (ϕ_c, ϕ_g, ϕ_i, γ, δ_k, θ_k)

pref1 = (β, l_λ, π_h, δ_h, θ_h)

These parameter values are used to define an economy of the DLE class.

econ1 = DLE(info1, tech1, pref1)

We can then simulate the economy for a chosen length of time, from our initial state vector \(x_0\)

econ1.compute_sequence(x0, ts_length=300)

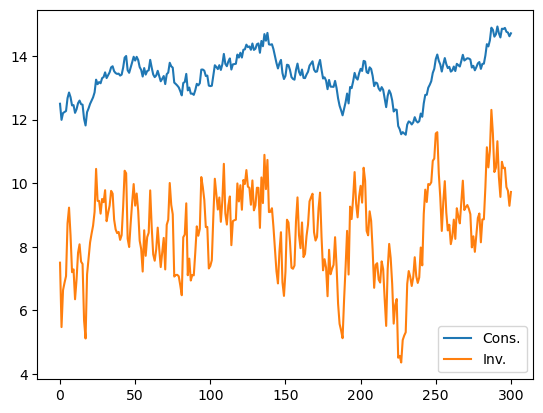

The economy stores the simulated values for each variable. Below we plot consumption and investment

# This is the right panel of Fig 5.7.1 from p.105 of HS2013

plt.plot(econ1.c[0], label='Cons.')

plt.plot(econ1.i[0], label='Inv.')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Inspection of the plot shows that the sample paths of consumption and investment drift in ways that suggest that each has or nearly has a random walk or unit root component.

This is confirmed by checking the eigenvalues of \(A^o\)

econ1.endo, econ1.exo

(array([0.9, 1. ]), array([1. , 0.8, 0.5]))

The endogenous eigenvalue that appears to be unity reflects the random walk character of consumption in Hall’s model.

Actually, the largest endogenous eigenvalue is very slightly below 1.

This outcome comes from the small adjustment cost \(\phi_1\).

econ1.endo[1]

np.float64(0.9999999999904767)

The fact that the largest endogenous eigenvalue is strictly less than unity in modulus means that it is possible to compute the non-stochastic steady state of consumption, investment and capital.

econ1.compute_steadystate()

np.set_printoptions(precision=3, suppress=True)

print(econ1.css, econ1.iss, econ1.kss)

[[4.999]] [[-0.001]] [[-0.016]]

However, the near-unity endogenous eigenvalue means that these steady state values are of little relevance.

18.3.2. Example 2: altered growth condition#

We generate our next economy by making two alterations to the parameters of Example 1.

First, we raise \(\phi_1\) from 0.00001 to 1.

This will lower the endogenous eigenvalue that is close to 1, causing the economy to head more quickly to the vicinity of its non-stochastic steady-state.

Second, we raise \(\gamma_1\) from 0.1 to 0.15.

This has the effect of raising the optimal steady-state value of capital.

We also start the economy off from an initial condition with a lower capital stock

Therefore, we need to define the following new parameters

γ2 = 0.15

γ22 = np.array([[γ2], [0]])

ϕ_12 = 1

ϕ_i2 = np.array([[1], [-ϕ_12]])

tech2 = (ϕ_c, ϕ_g, ϕ_i2, γ22, δ_k, θ_k)

x02 = np.array([[5], [20], [1], [0], [0]])

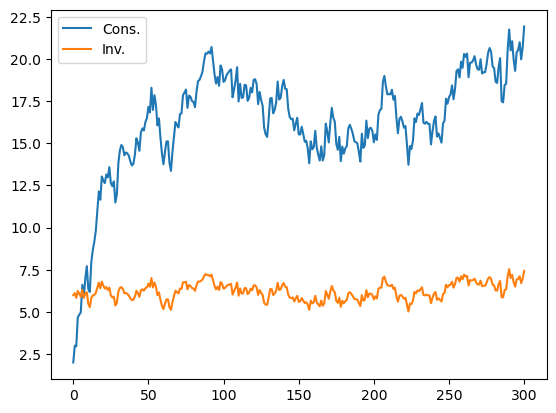

Creating the DLE class and then simulating gives the following plot for consumption and investment

econ2 = DLE(info1, tech2, pref1)

econ2.compute_sequence(x02, ts_length=300)

plt.plot(econ2.c[0], label='Cons.')

plt.plot(econ2.i[0], label='Inv.')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Simulating our new economy shows that consumption grows quickly in the early stages of the sample.

However, it then settles down around the new non-stochastic steady-state level of consumption of 17.5, which we find as follows

econ2.compute_steadystate()

print(econ2.css, econ2.iss, econ2.kss)

[[17.5]] [[6.25]] [[125.]]

The economy converges faster to this level than in Example 1 because the largest endogenous eigenvalue of \(A^o\) is now significantly lower than 1.

econ2.endo, econ2.exo

(array([0.9 , 0.952]), array([1. , 0.8, 0.5]))

18.3.3. Example 3: a Jones-Manuelli (1990) economy#

For our third economy, we choose parameter values with the aim of generating sustained growth in consumption, investment and capital.

To do this, we set parameters so that Jones and Manuelli’s “growth condition” is just satisfied.

In our notation, just satisfying the growth condition is actually equivalent to setting \(\beta(\gamma_1 + \delta_k) = 1\), the condition that was necessary for consumption to be a random walk in Hall’s model.

Thus, we lower \(\gamma_1\) back to 0.1.

In our model, this is a necessary but not sufficient condition for growth.

To generate growth we set preference parameters to reflect habit persistence.

In particular, we set \(\lambda = -1\), \(\delta_h = 0.9\) and \(\theta_h = 1 - \delta_h = 0.1\).

This makes preferences assume the form

These preferences reflect habit persistence

the effective “bliss point” \(b_t + (1-\delta_h)\sum_{j=0}^\infty \delta_h^jc_{t-j-1}\) now shifts in response to a moving average of past consumption

Since \(\delta_h\) and \(\theta_h\) were defined earlier, the only change we need to make from the parameters of Example 1 is to define the new value of \(\lambda\).

l_λ2 = np.array([[-1]])

pref2 = (β, l_λ2, π_h, δ_h, θ_h)

econ3 = DLE(info1, tech1, pref2)

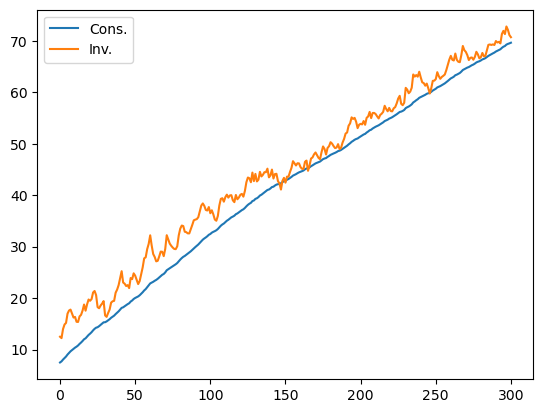

We simulate this economy from the original state vector

econ3.compute_sequence(x0, ts_length=300)

# This is the right panel of Fig 5.10.1 from p.110 of HS2013

plt.plot(econ3.c[0], label='Cons.')

plt.plot(econ3.i[0], label='Inv.')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Thus, adding habit persistence to the Hall model of Example 1 is enough to generate sustained growth in our economy.

The eigenvalues of \(A^o\) in this new economy are

econ3.endo, econ3.exo

(array([1.+0.j, 1.-0.j]), array([1. , 0.8, 0.5]))

We now have two unit endogenous eigenvalues. One stems from satisfying the growth condition (as in Example 1).

The other unit eigenvalue results from setting \(\lambda = -1\).

To show the importance of both of these for generating growth, we consider the following experiments.

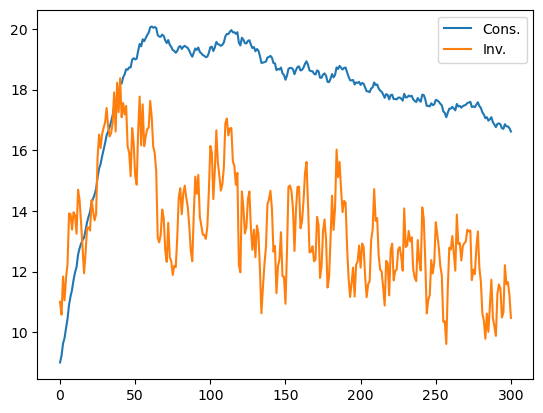

18.3.4. Example 3.1: varying sensitivity#

Next we raise \(\lambda\) to -0.7

l_λ3 = np.array([[-0.7]])

pref3 = (β, l_λ3, π_h, δ_h, θ_h)

econ4 = DLE(info1, tech1, pref3)

econ4.compute_sequence(x0, ts_length=300)

plt.plot(econ4.c[0], label='Cons.')

plt.plot(econ4.i[0], label='Inv.')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

We no longer achieve sustained growth if \(\lambda\) is raised from -1 to -0.7.

This is related to the fact that one of the endogenous eigenvalues is now less than 1.

econ4.endo, econ4.exo

(array([0.97, 1. ]), array([1. , 0.8, 0.5]))

18.3.5. Example 3.2: more impatience#

Next let’s lower \(\beta\) to 0.94

β_2 = np.array([[0.94]])

pref4 = (β_2, l_λ, π_h, δ_h, θ_h)

econ5 = DLE(info1, tech1, pref4)

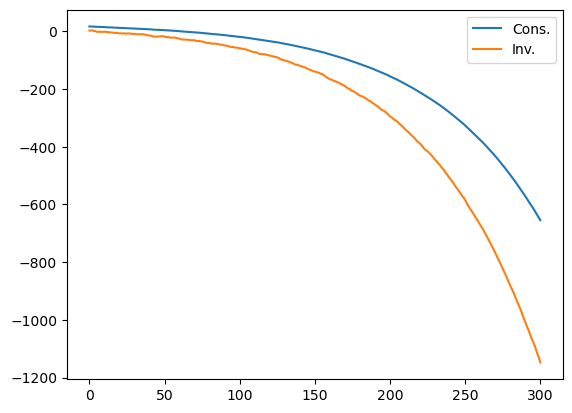

econ5.compute_sequence(x0, ts_length=300)

plt.plot(econ5.c[0], label='Cons.')

plt.plot(econ5.i[0], label='Inv.')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Growth also fails if we lower \(\beta\), since we now have \(\beta(\gamma_1 + \delta_k) < 1\).

Consumption and investment explode downwards, as a lower value of \(\beta\) causes the representative consumer to front-load consumption.

This explosive path shows up in the second endogenous eigenvalue now being larger than one.

econ5.endo, econ5.exo

(array([0.9 , 1.013]), array([1. , 0.8, 0.5]))